The Homefront

This is an abbreviated transcript from a series of recorded interviews

Vernell Sims-Rosenbusch: "I was in Olmos Drugstore at the soda fountain when WOAI radio interrupted music and announced that the Japanese had attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Everyone froze and listened as the announcer said that there was severe damage reported and large loss of life. I remember him saying, …several battleships have been sunk. I was shocked but I knew that we were at war."

Gladys Hearn: "I started work at Kelly [Army Air] Field as a clerk in September 1940. Before then I knew little about the European war. I heard a few things that prompted me to listen more carefully to the radio. There seemed to be an international unrest in the papers and on the radio. Most of what you heard was the Nazis this and the Nazis that. Roosevelt claimed America was not going to get involved in the European war.

In 1941, Robert Taylor starred in a movie that stirred some controversy. Flight Command, I think it was, was a pre-war Navy flyer show and introduced the National Defense Reserve. About that same time Lend-lease was starting up. People didn't want to think about war. We had enough problems with the depression. Before the war, I heard of soldiers being refused service in restaurants because of anti-war sentiments. Of course, that changed after Pearl Harbor.

For myself, I was just happy to be working and in my book that made FDR alright by me. On the other hand I had no desire to join the WACs, Waves or any military.

Pearl harbor was the first shock that America was at war, but for me it was a week or so after D-Day. Telegrams flooded San Antonio about the deaths and wounded. I remember a neighbor screaming and weeping uncontrollably when her telegram arrived, and for a long time, struggling with the emotional throes over the loss of her husband. He had been only a transport pilot in England and she believed he would not be in combat. To complicate matters, their first child had arrived only months before. She kinda went nuts. I never realized how wretched emotional pain could be and this is probably why I never married. As for the war overall, I didn't understand much about it until it was finally over.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: "I lived in Fredericksburg Texas when it was still a small town during the [19]40s. I was sixteen years old when the Japs bombed Pearl Harbor and everyone began gossiping about the Japs, Italians and Germans. Before then I knew nothing.

... Are you asking about the Japanese internment? I didn't really care back then and still don't. It was war and war isn't a time to be politically correct. Haven't you ever heard of the America First organization or the German-American Bund? My parents were German and my first name is actually Anneliese. We were not members of the Bund, but my father disagreed when the Bund hinted the idea that British and French were really the bad guys. The Bund was persuasive but father refused to listen. Too many memories of World War I haunted him. If the Bund could have manipulated the politics enough you'd be speaking German with me right now. For that matter, we normally spoke German in our home, but when Germany invaded France, both mother and father stopped. They never spoke another word of German and neither have I.

Did you know that German-Americans were interned? The FBI came by and spoke to my parents several times. Once they asked me questions. We knew the FBI had spoken to all the neighbors and anyone we associated with. They asked if we would volunteer to be interned for our own safety. My father said that he didn't believe we were in any danger if we remained where we were and didn't travel. The FBI searched our house and father's shop. They were satisfied that we weren't a threat but they asked father to keep a ledger of radio parts he received and any radios he fixed.

Later we discovered that some relatives, who were members of the Bund- a family on my mother's side- had been interned. By the end of the war, over 10,000 German descendents had been interned at Ellis Island, and like the Japs, lost their homes, jobs and everything. The ones we knew accepted their situation as a fact of war and let it be.

German-American internees celebrate Thanksgiving 1942 at Ellis Island

Raymond Rosenbusch: "The depression? ...I can't describe how bad the depression was in a way you'd understand. Not that there wasn't a reasonable amount of food or clothing but there was no money for either. I was the oldest and had to leave home. There was no food for my brothers and sisters as it was. I had no problem working hard but there was no work. People today cannot understand what I'm saying because there are jobs, but they won't take them. Maybe not great jobs, there is work. Before I joined the Conservation Corps, I walked to farms for three days looking for work. No food either, and none was offered. Back then you didn't bother asking. I finally found a job as a hired hand. That job paid only in meals and a place to sleep.

When I went to work in the Conservation Corps I went to San Antonio in 1938 for a public works project on the Riverwalk.

... In the late [19]30s, I think *America First and the *German-American Bund pointed out how Hitler was a purposeful, straight-laced tea-toter while Roosevelt and Churchill were men of leisure, guzzling bourbon and scotch, smoking their fancy cigarettes and cigars [respectively]. Me, being from the Bible-belt, bought into that for awhile.

... sure, the Japs were running rampant across the orient but those places were a million miles away. In 1940 I was aware that FDR* was warning the Japs to leave China and the Far-East alone, but the occasional radio or newspaper editorials pointed out that it was not an American problem. Personally, I still wasn't sure if we even had a bone to pick with the Germans.

... Poland? A lot of people bought that France and Britain were the bad guys when Germany invaded Poland. We understood that Poland attacked Germany and they had the right to defend themselves. I kinda thought the Germans were being picked on because of the past, meaning World War I. Back then we called it the Great War.

In early 1941 I joined the Army after Hitler attacked Russia. That was my wake-up call. Things were changing fast. First I trained as a radio operator, but since I spoke German I was offered sergeant to be a translator/ interpreter. I met Vernell when I was stationed at Fort Sam [Houston]. Her folks didn’t take kindly to me being a soldier boy, or yet for that matter, a Kraut (German) descendent.

Before Pearl Harbor, a few people treated military personnel badly. Our uniforms were the most we could afford and some restaurants posted signs saying ‘no coloreds and no soldiers.’ It was politics and wearing a military uniform was kinda agreeing with *FDR on his European policy, like lend-lease. Unemployment was still high, so everyone just wanted the depression solved and forget the rest of the world. Besides, a lot of people believed that Hitler was an okay joe and any problem of Europe's was their problem.

... about Pearl Harbor? I was shocked! There was nothing that could have prepared me for that. A few days before Pearl Harbor I remember a big hoopla about *FDR's war plans to invade France and Germany. A lot of people were very angry, but then Pearl Harbor changed everything over night.

On December 4 1941, the Tribune denounced Franklin D. Roosevelt as a war monger. Three days later, the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor.

Gladys Hearn: Back then, people were probably more patriotic. … after Pearl Harbor, there was mad rush to join up. You would hear of men-folk from entire families signing up. The Sullivan brothers were one example but there was a grandfather, father and son who all joined the Army Air Force. The grandfather ran a PX (military store). The son became a fighter pilot and his dad became an airplane mechanic. At one time, the father and his son were at Kelly Field and there was a newspaper article about the family. Movie stars joined too. I remember a big heyday when Jimmy Stewart came to Kelly Field. He was a bomber pilot and it disrupted things a bit even though they tried to keep it quiet. But when Clark Gable joined the Army Air Force we girls kept hoping he would come to Kelly Field.

Raymond Rosenbusch: Vernell and me talked about getting married. I was sorely tempted but I said no. I had seen girls who followed their men to their new posts. Rents were over-priced. Even with the family allotment, soldiers made next to no money so the wives had to fend for themselves and their children. Some conditions were unbelievable and there were people who would take advantage of them. After Pearl Harbor, women and their children would spend a week in a train station trying to get to their husband’s next post. Transportation services were prioritized so those traveling on non-war-essential business were at the bottom of the barrel. Another reason was, I had good chance of being killed in a war.

... Well, the last reason is an obvious one that I've never told Vernell. Rosenbusch is a Kraut surname and not likely to draw any favors.

... Bitter? No. Nothing to be mad about. My parents were German and I had an uncle interned. If I hadn't joined the Army, I'm sure I would have been interned and rightfully so.

... war is not about justice, right, wrong or even fair. It's about ideology and choosing which ideology you're willing to die for, so you can have a chance to live by it. Under any tyranny is a bad way to live. Only the ideology of a republic appeals to me.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: I wasn’t dating but my mother kinda had her eyes set on a young man for me who was attending a university. He was headed to law school and came from a well to do German-expatriate family. Like most people, we had struggled through the depression and mother was more interested in me getting with a well-heeled man than a big-hearted one. Of course, being an American teenager I had other ideas other than letting my mother pick my husband. I let it go on a little as an excuse for me to attend college part-time.

Gladys Hearn: Did you ever see Judy Garland and Robert Walker in The Clock? No? Robert Walker plays a corporal on a 48 hour pass before being shipped off to the war. He meets Judy Garland, an office worker, falls in love and marries her. It was just like that.

When the war got into full swing the old taboos of class, family permission and courting were gone. I saw farm-boy fighter pilots marrying classy dames from old-money families. Some would meet and get married less than a week. The girl would end up conceiving a ‘good-bye baby’ and a little later, a dead husband. There were quite a few in the widow & orphan crowd. We called those ‘Hit & Run’ marriages. I guess for the moment everyone got what they wanted.

A pilot from Randolph asked me to marry him. We didn’t love each other but he said he knew he'd be dead within a year or so, and I kinda knew he would be too. He just wanted to have some fun at life, but I said no. He married another girl and they had a great time. She discovered she was pregnant after he left for Europe. He was killed soon over Germany while flying a B-24. It hit her the hardest when their son was born.

There were also girls called ‘Allotment Annies’. They married GIs for the fifty dollar family allotment and the $10,000 insurance. The post office helped catch some of them. The post office would get a little suspicious when these girls would collect more than one government check each month, often addressed to the same girl or with only a different last name. Every so often, the newspaper would announce the arrest of these girls for polygamy.

Also there were V-girls that the newspapers called 'Patriotutes'. Victory girls, mostly called V-girls by everyone, were teenagers that dated soldiers. The dates also included bedding down with the soldier. The newspaper once reported a big fight between some prostitutes and V-girls near Funland Park on Broadway over the soldiers they were ‘dating’. I didn't consider Allotment Annies much different than the V-girls, or the Hit & Run girls for that matter. I think that's when social values took a nose-dive.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: I'm not saying that we didn't have bad people, but back then people wouldn't lie or steal easily. I think very few, if any, parents would lie and say a child was under twelve or ten to get a meal or bijou ticket cheaper. The parent knew it set a bad example for the child. People should remember, it's your words those little ears regard.

... even the word "pregnant" was considered too graphic, a little too racy to use in polite company. So we had all that talk about stork visits or simply 'expecting.'

Of course we didn't have the obscurity cities possess today...

... I knew from the get-go that if I set off to no good, chances were I'd run into someone; my brother's little league coach; Widow Miller from up the street; my sister's piano teacher, or some nosy biddy from church. Everyone knew my name and my parents' phone number. I still remember it was 8224 in town. Long distance it was PAlace 4-8224. To the long distance operator connecting it, that's P.A. 4-8224. Ever hear Glenn Miller's song, PEnnsylvania six-five thousand?

The idea of 'coast to coast travel' once held all sorts of excitement and now means almost nothing. Now we take the word 'worldwide' for granted. That floors me. People today take so much for granted. Privileges that were once earned are now considered rights. Some people believe because they have the money, they have the right. They forget about being responsible. Just because you have the money for a fast car doesn't give you the right to break the speed limit or be reckless.

Vernell Sims-Rosenbusch: I had no intention in being a career girl, but for the war effort I went to work for North American Aviation in Dallas.

After a two-week school I was rushed onto the P-51 Mustang assembly line. I began on the bucking bar and quickly found myself on the rivet-gun. Not only was the pay better for those who performed but you were given the critical jobs.

In no time I was assigned to wing assembly, in particular, the spar which is the most critical part of the airplane. On my team were all girls. Only our supervisor was a man.

Mr. Burkhardt was my father’s age and he treated us like his daughters. He found my team an apartment that we could share. We did a lot together, coming to work together, double, or rather triple-dating and more.

Everything was extreme, work, play, laughing, and the crying ...

Women could negotiate small spaces and proved more adept at riveting than men.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: ... work in a war factory? Not with my parents' accents and background. We were satisfied to stay put in my hometown. Father had plenty of business in his fix-it shop, and mother knew better than to venture beyond where we were known and trusted.

We grew a victory garden in the back yard and raised rabbits in hutches. Entertainment was books, and in the evenings, some radio shows but you still had to use your imagination.

... every girl I knew could sew. We would chat about Butterick, McCall and Simplicity patterns. Of course, just about everything is store-bought these days, but once it was bragging rights to have a store-bought dress or some store-bought candy. People were more self-reliant back then. People were more interested in what you could do rather than what you could buy.

Today, people buy what they think makes them people of real meaning. Girls shamelessly chase boys with fancy cars and pretty clothes. They don't give any thought to whether he is family material. I guess that's 'cause divorce comes too easy today. Back then divorce was a soiled word and spoken only in a whisper. And no one is called a "divorcee" anymore. Certainly not a 'gay' divorcee. Come to think of it, 'confirmed bachelors' and 'career girls' are long gone, too.

Raymond Rosenbusch: Meals in the army weren’t bad. I was a young man during the depression and it was better than not eating at all. Ketchup was used liberally, especially on eggs, which were powdered. That's where putting ketchup or chili on scrambled eggs started. Breakfast, I think was the worst. Mostly 'cause the food was cold by the time you got to it. The eggs were kinda watery, kinda chalky sometimes, and always had a funny gray look to 'em. Other than breakfast, the food was mostly hot and edible.

Eating in restaurants could be difficult for enlisted men. Officers were welcomed everywhere but if you had stripes on your sleeves most places suddenly had no tables available. A Mexican cafe at El Mercado (the market in San Antonio) was a hole in the wall, but they welcomed anyone and had good food, so it became a favorite of soldiers. I remember that they offered a dinner plate of two enchiladas, a tamale, Spanish rice, refried beans with a coupla tortillas for two-bits (twenty-five cents).

In different parts of the country, some foodstuff like ice cream or milk shakes required soldiers to sign a ledger with your name, rank and service number. I’m not sure what good it did. Mostly this was done in small towns like Kerrville.

Gladys Hearn: I ate at home and my mother did all the shopping, so rationing didn’t affect me too much. Sometimes we would drive to Del Rio where just across the border you could buy anything because Mexico wasn’t at war and they had no rationing. We would fill up our gas tank, buy steaks, roasts, liquor and leather purses, shoes and boots.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: Back then we owned less but had more. Before the war we did kinda okay and put a little money away for a rainy day. Only hotels and fancy restaurants had 'refrigerated' air so the windows in houses stayed up, and when a child cried outside a dozen mothers would come running.

I knew more people back then and knew them better. A family name had value and most people's word was gospel. My parents often said, 'Remember who you are,' meaning: don't bring shame to the family name.

... in the [19] 30s and 40s, a teacher, like a policeman, was a person of respect. If a teacher said a child was deserving of a 'D,' that was the end of it. My son-in-law just retired from teaching, mostly 'cause of his frustration with parents. They don't want to understand when their child is substandard in education. And they don't care. They just want to lie to themselves and proclaim him, or her, deserving of an 'A.' They will fight with the teacher rather tell their child to get off their lazy butt and hit the books.

... it's no wonder the schools occasionally hire a bad teacher who gives the others a bad name. Schools have to fill in the blanks wherever they can ... About the late '60s, when my son-in-law became a teacher is when all of that really started to change. It's about values and respect.

Occasionally I did read in the newspaper about V-girls and other such debauchery, but there was discretion. Radio was reluctant to speak of such things. Manners are traffic rules for good society and back then, decadence was kept away from innocent eyes and ears. Swearing ranked you as trash. Today, the radio people try to out-do one-another with filth.

I remember that my brother got BB gun for his eighth birthday. God forbid you give a terrifying gift like that today. Yet today, children play violent computer games and see nasty things on television, but that's considered okay. Then they wonder why teenagers are so violent and promiscuious.

Vernell Sims-Rosenbusch: Sometimes we worked over-time so we could eat in the canteen again. The meals were very good and plentiful. Away from work you could get hamburgers easy enough, but sometimes no cheese or milk shakes though. Because the name hamburger sounded a bit German, a lot of places were calling them ‘Liberty-burgers. Sometimes diners would run out of food and have to close for the day. I read about this in big cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles, but it didn’t happen too often in Dallas or San Antonio.

Anne Dietz-McLeary: A loaf of bread cost about 15 cents and it was safe for my eight-year-old brother to go to the store by himself ...

... back then I loved to climb into a fresh bed, 'cause sheets were dried on the clothesline instead of a stale dryer ...

... the only hazardous material you'd hear about was a patch of grass burrs at some vacant lot.

People generally lived in the same hometown with their relatives, so childcare to me meant someone's relatives. All adults and parents were respected and their rules were law.

... children did not talk back.

... certain behavior was expected and nothing less was tolerated.

... so all the dads could fix things. Once, before the war, some mothers made the fathers get together and they re-roofed Widow Miller’s house in less than a day. It became a picnic affair and we all had a lot of fun too.

I started college part-time in 1944.

... my instructors were Miss Mills, Mr. Nelson and Professor Cohen, but Celia, my great-granddaughter out in California, says she calls her high school teachers Ms. Becky or Mr. Jason. Once, there was proper respect for a title, and I don't mean just yes sir or yes ma'am, and Mister or Mrs. We respected that people, especially doctors or professors, worked hard to achieve their distinctions.

... it was a different time back then. That’s when America had an ethic and an innocence that we'll never get back.

The Homefront

according to research

The contiguous United States had only been attacked twice during World War II— once when a Japanese submarine shelled Santa Barbara with little damage and when a Japanese balloon-bomb killed a family of six at a picnic— but the war filled every facet of American life.

Seven months before Pearl Harbor, ground broke for the construction of a massive B-24 factory at Willow Run. The single structure covered 67 acres and by the end of the war, a bomber rolled out every hour. At the Kaiser shipyard, a ship was built in as little as 80 hours and thirty minutes.

The War Production Board ordered factories to cease making rubber boots and merry-go-rounds and begin making pontoons and gun-mounts. Lionel (toy trains) began making bomb-fuses. Thirty percent of the cigarette production went to the military. People retread their car tires with old leather soles.

Rubber supply suffered the worst. Gasoline rationing was implemented more to conserve rubber tires. However, necessity is the mother of invention and by 1944 synthetic rubber eased America’s rubber hardship.

Conservation became the battle-cry on the home-front and scrap drives were in constant motion. While junk metal, like aluminum and steel, had obvious value, disposables like bacon grease were needed for manufacturing ammunition, and old silk or nylon stockings were collected for powder bags for naval guns. In 1942, the Boys Scouts succeeded in bringing to a temporary halt, the paper drive, by glutting paper mills. Used paper was needed for packing ammunition for transport.

The nation also mobilized Victory gardens into action. By 1943, 30 percent of the food consumed by the nation came from Victory gardens. Housewives became more nutrition conscious while discovering unfamiliar vegetables such as Eggplant and Swiss Chard. Victory gardens contributed another benefit to the home-front— healthy citizens.

Rationing

Office of Price Administration

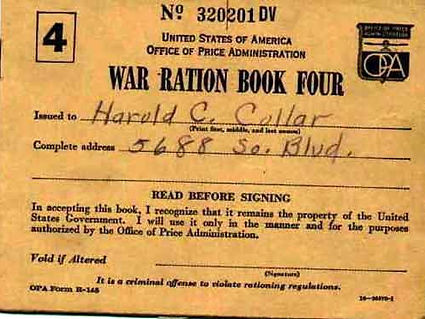

Because military supply transports were often shot down or sunk, the only way to insure adequate supply was to send many times the amount required to the war front. At home this created shortages, both because of the lack of manpower and higher demand; therefore a U.S. federal agency titled the Office of Price Administration was established to prevent wartime inflation in World War II.

In April 1942, the OPA declared a general maximum-price regulation that made prices charged in March 1942, the maximum price for most commodities. This included residential rents.

Still, prices rose nearly four-percent a year from 1942 to 1945. However, this understates real inflation because the quality of many goods declined during the War. Woolens were scarce, and women's nylon stockings disappeared. Women's clothing relied on fewer materials and skirts became shorter and narrower. Victory suits for men were a sad attempt to save material. Vests, pocket flaps, elbow patches on jackets, and even cuffs on pants were eliminated from men's trousers.

The Federal government directed Americans to cut back on foodstuffs and consumer goods. Eventually the OPA was authorized to ration consumer goods such as tires, automobiles, sugar, gasoline, fuel oil, coffee, meats, and processed foods. However, rationing was not limited to food. Leather goods were scarce. Often it was "buyer beware" as well. Unscrupulous people sold fake goods like cardboard shoes touted as leather. These were excellent imitations until they ran afoul in their first puddle of water.

Prices still continued to rise and new initiatives to guarantee compliance and people needed ration books to make purchases. Now consumers had to keep an eye on two prices: one in dollars, the other in points as availability changed.

To implement rationing, people were issued ration books in the district where they lived. Since most people consistently visited a particular butcher or market, this merchant was responsible for monitoring the needs of his regular customers. In turn, the families would surrender their used ration books, enabling the merchant to acquire more products

These regulations were gradually modified by the OPA until almost 90% of the retail prices were frozen. To aggravate the situation, a government order directed the auto industry to shift completely to producing vehicles for the military. Many consumer goods made of metal either disappeared or other materials were substituted for metal.

Rationing frustrated many Americans. For the first time in years, they had money to spend, but there were few goods available. This frustration kept mounting until the end of the war. Still, Americans fared better than the rest of the world with coupon points dividing the available supply.

Their father in the military and their mother working in a war factory, two girls do the family shopping.

Notice the price tag and the smaller ration points tag.